A River Runs Through It...

But what runs through the river?

|

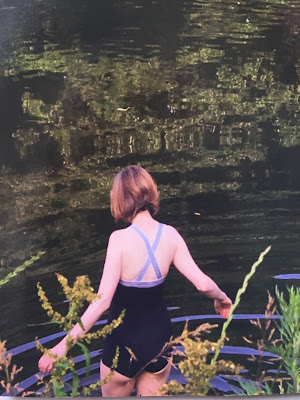

| Photo credit: Frankie Sinclair |

I went for a swim on Sunday morning. Trees shaded the sultry headstart to a blazing hot day. Sunlight winked off the petrol iridescence of a damselfly as I followed the emerald flow of waterweed downstream along the River Granta in Cambridgeshire.

Passers-by asked me if the water is clean. I smiled. I frowned. I hesitated way too long. Well...

I don't put my head underwater. I don't go in if I have scratches or insect bites. I don't swim after rain. Because in 2021 the UK is sadly backward in its environmental care. If I feel vaguely unwell the day after a swim have I picked up a bug, or am I just sick and tired of this appalling reality?

In 2017 I celebrated midsummer with a swimming break on the River Wye, reputed then to be one of the cleanest rivers in the UK. A dark past of industrial pollution seemed to have been rinsed clean. But the film Rivercide that premiered with a live broadcast on a sunny evening last week tells a different story. Tragically, since my trip the Wye has become polluted by new industry as large scale chicken faming proliferates along its banks. The emerald flow of water crowfoot (Ophelia's buttercup) is grey and slimy and choked. Writing in the Guardian, campaigner and writer George Monbiot explains: "Water that should be crystal clear has become a green-brown slop of microscopic algae because of industrial farm waste"

I love river swimming. I love getting right into the heart of my local geology and wildlife, not just plodding by on two legs. It's a quick dip into another dimension, a mini adventure close to home. 'My' river Granta is said to be as valuable as the Amazon for its rarity and specialist ecology. It's a chalk stream, one of only 260 worldwide (224 of them are in England).

On midsummer day 2021 the Friends of the Cam gathered for a Declaration of the Rights of the River Cam to flow, to be free from over-abstraction and pollution, to be fed by sustainable aquifers, to perform essential functions within the ecosystem.

I like to immerse myself in escapist lyricism of literature about place and natural history. And my daily walks or dips are nourishment I can't ever do without. But there's a new shift towards action - and words about action because, as Rebecca Solnit says here "We need a new word for that feeling for nature that is love and wonder mingled with dread and sorrow, for when we see those things that are still beautiful, still powerful, but struggling under the burden of our mistakes".

Ophelia by Sir John Everett Millais (1851-2)

Comments

Post a Comment